The US passed a grim milestone in 2021: for the first time, more than 100,000 people in the United States died of a drug overdose over a 12-month period, making overdoses the #1 preventable cause of death. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 40.3 million people aged 12 or older had a substance use disorder (SUD) within the past year, while only 4 million people received any form of SUD treatment (SAMHSA, 2021a).

For those who do receive treatment, finding evidence-based care is a tremendous challenge:

Treatment is expensive, and insurance coverage for SUD and mental health treatment remains extremely low despite longstanding parity legislation requiring equal coverage of physical and behavioral health services. The quality of the treatment provided is also very inconsistent: while Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is recognized by federal agencies and addiction medicine educators as the gold standard for the treatment of substance use disorders (SAMHSA, 2021; Mee-Lee, 2013), a recent study found that 60% of SUD treatment centers in the US do not offer MAT for opioid use disorders (OUD) at all, and only 1.3% offered all three FDA-approved medications for OUD (Huhn, 2020).

Some institutions implement an abstinence-only approach (Lee, 2015; Lee & O’Malley, 2018). According to the abstinence-only model, a patient who is not aiming to fully abstain from using any substance during and after the treatment period is overly resistant and cannot be treated (Miller & Rollnick, 1991), nor can they receive support services such as housing or psychosocial support (Lee, 2015). As a result, the SUD treatment pathways exclude those most in need of treatment and instead facilitate access for clients who are able to show an unrealistically high level of readiness for change (Lee, 2015; Lee & O’Malley, 2018). While abstinence from substance use has traditionally been seen as a measure of success in SUD treatment, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s working definition of “recovery” does not include the word “abstinence” (SAMHSA, 2020).

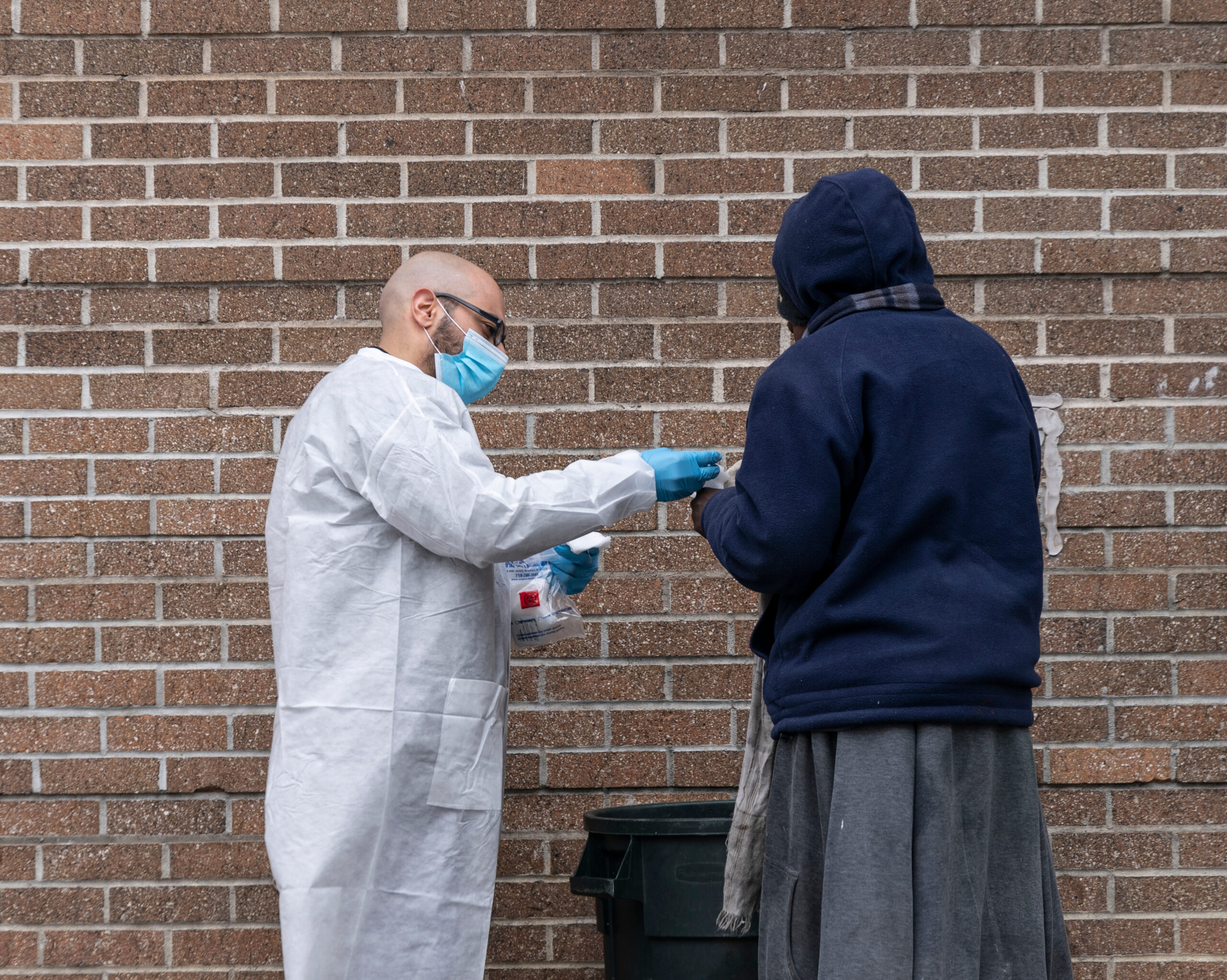

Harm reduction with abstinence as a goal contrasts with an abstinence-only model. Harm reduction is a set of evidence-based public health practices that aim to reduce the negative consequences of substance use, even without total abstinence. Examples of harm reduction activities for OUD patients include:

- Reducing the risk of overdose and early death by providing Fentanyl test strips and Naloxone kits for overdose reversal

- Reducing stigma and increasing access to health and social services by facilitating counseling and providing compassionate care including Motivational Interviewing and low-threshold access to MAT

- Reducing the risk of sexually-transmitted infections (STI) such as HIV and hepatitis by providing STI testing and access to PrEp

The abstinence-only approach and its reliance on the “moral failing” model of addiction stand in opposition to our modern understanding of addiction as a brain disease, as it is categorized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-V) (APA, 2013) and by the World Health Organization (Volkow et al., 2017). Notably, the moral and disease models are blended in Alcoholics Anonymous and many other 12-Step programs, which view alcohol misuse as an illness but also emphasize a long list of “defects of characters” that participants must overcome (Marlatt, 1985).

As healthcare providers and educators, the magnitude of the opioid epidemic compels us to take accountability for the care we deliver to patients rather than blame patients for their disease. Harm reduction approaches have been proven to save lives and are now embraced by all major agencies (WHO, CDC, SAMHSA, ONDCP) overseeing organizational responses to the opioid crisis. The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) has removed most barriers for primary care providers to treat OUD patients with buprenorphine. In December, the Federal Government announced a $30 million investment in syringe service programs and other harm reduction measures. And HHS now endorses Contingency Management, which offers financial incentives for healthy behaviors such as lowering use and adhering to treatment.

As the opioid crisis continues to ravage our communities, it is crucial that healthcare professionals are trained to provide access to evidence-based care that reduces risk overdose deaths and minimizes the social, legal, and medical consequences of using opioids or other substances. Abstinence from substance use should remain an ideal outcome of treatment rather than its main strategy.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Beletsky L, Wakeman SE, Fiscella K. Practicing what we preach—ending physician health program bans on opioid-agonist therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(9):796–8. Pmid:31461593

Huhn AS, Hobelmann JG, Strickland JC, et al. Differences in Availability and Use of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Residential Treatment Settings in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920843. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20843

Lee, H. S., & O’Malley, D. (2018). Abstinence-Only: Are You Not Working the Program or Is the Program Not Working for You?. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 18(3), 289-304.

Marlatt, G. (1985). Relapse prevention: Theoretical rationale and overview of the model. In. G. Marlatt & J. E. Gordon (Eds.), Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: The Guilford Press.

Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman MJ, Gastfriend DR, Miller, eds. (2013). The ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-Occurring Conditions. 3rd ed. Carson City, NV: The Change Companies; 2013. Copyright 2013 by the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Miller, W., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2020). Substance Use Disorder Treatment for People With Co-Occurring Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 42. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP20-02-01-004. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2021b). Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series No. 63 Publication No. PEP21-02-01-002. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021.

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, Beletsky L, Keyes KM, McGinty EE, et al. (2019). Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 16(11): e1002969. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002969

Tatarsky, A. (2002). Introduction. In A. E. Tatarsky (Ed.), Harm reduction psychotherapy: A new treatment for drug and alcohol problems (pp. 1-15). Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson Inc.

Volkow, N. D., Poznyak, V., Saxena, S., Gerra, G., & UNODC-WHO Informal International Scientific Network (2017). Drug use disorders: impact of a public health rather than a criminal justice approach. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(2), 213–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20428

Elodie Adam

Author